Sir William Rowan Hamilton famously discovered the key rules for quaternion algebra while walking with his wife past a bridge in Dublin in 1843. A plaque now commemorates this event. I needed to use the quaternion rotation operator recently and while digging around the literature on this topic I noticed that a lot of it is quite unclear and over-complicated. A couple of simple, yet vital, ideas, if they were spelt out, would make key results seem less mysterious but these never seem to be mentioned. The vector notation often used in this area also seems to over-complicate things. In this note I want to record some thoughts about the quaternion rotation operator, bringing out some key underlying ideas that (to me) make things seem far less mysterious.

Quaternions are hypercomplex numbers of the form

In many ways (as I will show below) they can usefully be thought about using familiar ideas for two-dimensional complex numbers in which

.

In the case of quaternions, the identities discovered by Hamilton determine all possible products of

,

and

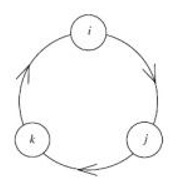

. They imply a cyclic relationship when calculating their products (similar to that of the cross products of the three-dimensional basis vectors i, j, k, which is why authors often use these basis vectors when defining quaternions).

Taking products clockwise one obtains

and taking products anticlockwise one obtains

This algebraic structure leads to some interesting differences from the familiar algebra of ordinary two-dimensional complex numbers, particularly non-commutativity of multiplication. Technically, one says that the set of all quaternions with the operations of addition and multiplication constitute a non-commutative division ring, i.e., every non-zero quaternion has an inverse and quaternion products are generally non-commutative.

I was interested to notice that one way in which this algebraic difference with ordinary complex numbers manifests itself is in taking the complex conjugate of products. With ordinary complex numbers and

one obtains

since

and therefore

but this is the same as

With the product of two quaternions and

we get a different result:

In words, the complex conjugate of the product is the product of the complex conjugates in reverse order. To see this, let

Then

Therefore

But this is the same as

The complex conjugate is used to define the length of a quaternion

as

To find the inverse of a quaternion we observe that

so

For a quaternion

let

A key result that helps to clarify the literature on quaternion rotation is that

This seems mysterious at first but can easily be verified by confirming that when the term on the left hand side is multiplied by itself, the result is :

This result means that any quaternion of the above form can be written as

This is just a familiar two-dimensional complex number! It therefore has an angle associated with it, given by the equations

We can express the quaternion in terms of this angle as

If is a unit quaternion (i.e.,

) we then get that

This is the form that is needed in the context of quaternion rotation. It turns out that for any unit quaternion of this form and for any vector the operation

will result in a rotation of the vector through an angle

about the vector

as the axis of rotation. The direction of rotation is given by the familiar right-hand rule, i.e., the thumb of the right hand points in the direction of the vector

and the fingers then curl in the direction of rotation.

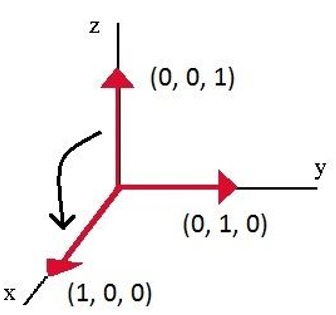

As an example, suppose we want to rotate the vector through

about the vector

in the sense of the right-hand rule.

Looking at the diagram above, we would expect the result to be the vector . Using the quaternion rotation operator to achieve this, we would specify

The resulting vector would be

This result is interpreted as the vector which is exactly what we expected based on the diagram above.

Note that to achieve the same result through conventional matrix algebra we would have to use the rotation matrix

Setting and applying this to the vector

we get

This is the same result, but note that this approach is more cumbersome to implement because there are different rotation matrices for different axes of rotation and for different rotation conventions. The above rotation matrix happens to be the one required to achieve a rotation about the y-axis using the right-hand rule. In general, the correct rotation matrix would have to be computed each time to suit the particular rotation required. Once the angle of rotation and the axis of rotation are known, the quaternion rotation operator is easier to specify and implement.