A Laplace transform of a function

is defined by the equation

The idea is that a Laplace transform takes as an input a function of ,

, and yields as the output a function of

,

.

In many applications of this idea, for example when applying a Laplace transform to the solution of a differential equation, we need to find the inverse of the transform to obtain the required solution. This can often be done by consulting tables of Laplace transforms and their inverses in reference manuals, but we can also invert Laplace transforms using something called the Bromwich integral. I want to explore the latter approach in this note, as it involves the useful trick of solving integrals by converting them to contour integration problems on the complex plane. I also want to record a useful trick for changing the order of integration in double integrals which is employed in the proof of a convolution theorem for Laplace transforms.

Differential equations can be solved using Laplace transforms by finding the transforms of derivatives ,

, etc. To find

, we use the above definition of

and integrate by parts as follows:

where for simplicity we have written and

.

To find , we think of

as

and substitute

for

in (2) to get

Continuing this process, we can also obtain the transforms of higher derivatives. Using these results, we can now solve differential equations. For example, suppose we want to solve

with initial conditions and

. We simply take the Laplace transform of each term in the equation. We get

Using the given initial conditions, the left-hand side of (5) reduces to . We can obtain the Laplace transform on the right-hand side of (5) by consulting a reference table, or by integrating. Following the latter approach, we integrate by parts once to get

and then integrate by parts again to get

Combining these, we get

Alternatively, from standard reference tables we find that

Therefore

Using these results in (5) we get

and so

Recall that , so what we need to do now to solve the problem is to apply an inverse Laplace transform to both sides of (7). This would give

We could evaluate the right-hand side of (8) using the formula from the reference table in (6). We see from this formula that we need ,

, so we can immediately conclude that

This is the required solution to the second-order differential equation in (4) above. What I want to do now is explore the Bromwich integral for Laplace transforms, and use it to confirm the answer in (9) by obtaining the inverse Laplace transform of via the residue theorem from complex analysis.

In the definition of the Laplace transform in (1) above, we now let be a complex number, say

. Then the Laplace transform becomes

where for some real

. [We must have some restriction on

to make the integral converge at infinity. The restriction depends on what the function

is, but it is always of the form

for some real

. To illustrate this idea, consider the case

. Then we have

The final equality here holds only for , because otherwise

would not vanish at the upper limit of the integral. If

is complex, then

would be required in this case]. Now, (10) has a form similar to that of a Fourier transform

with inverse

in (10) corresponds to

in (11), and

in (11) corresponds to

in (10). Pursuing this analogy with a Fourier transform, the inverse transform for (10), corresponding to (12), would then be

Using the definition of , we can write this as

for . Since

is a constant in this setup, we have

, so we can write (14) as

where the notation means that we integrate along a vertical line in the

plane. [This can be any vertical line on which

as required by the restriction on

]. The integral (15) for the inverse Laplace transform is called the Bromwich integral.

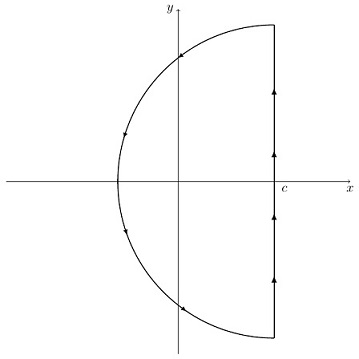

To use (15) to evaluate for a given

, we exploit the fact that we can evaluate integrals in the complex plane by using the residue theorem. We imagine a contour consisting of a vertical straight line and a semicircle enclosing an area to the left of

. We evaluate (15) by using this contour.

We restrict to be of the form

, with

and

polynomials, and

of degree at least one higher than

. The value of the integral around the contour is determined by the singularities lying inside the semicircle, in accordance with the residue theorem. Specifically, the residue theorem says that the integral around the contour equals

times the sum of the residues of

at its poles. As the radius of the semicircle goes to infinity, the integral along the straight line becomes an improper integral from

to

. However, the integral around the semicircle has the radius appearing to a higher degree in the denominator than in the numerator, so this integral goes to zero as the radius becomes infinite. We are left only with the improper integral along the straight line, and the residue theorem then assures us that this must equal

times the sum of the residues of

at its poles . Cancelling the factor

from (15), we conclude that

So, to find from the Laplace transform

, we simply construct the complex function

, and then sum the residues at all the poles of this constructed function. Note that we must include all poles in (16), i.e., we must choose

such that all the poles of

lie inside the contour to the left of the vertical line we are integrating along. To find the residues at each pole, we can use the following rule:

When a function has a pole of order

at

, the residue at this pole can be obtained by multiplying

by

, differentiating the result

times, dividing by

, and evaluating the resulting expression at

.

We can now apply this approach to find the inverse of the transform

We have

This has a pole of order 5 at . Therefore, multiplying by

we get

, differentiating this result

times we get

, and dividing by

we get

. Finally, evaluating the result at

gives the answer

which exactly matches the answer we got in (9) above.

We also have a convolution theorem for Laplace transforms, the proof of which I want to explore here. The convolution theorem says that the Laplace transform of a convolution of functions is the product of the Laplace transforms of the individual functions in the convolution. So, if and

are functions, and

and

are their corresponding Laplace transforms, then the convolution theorem says

where

is the convolution of and

. To prove (17), note that from the definition of a Laplace transform in (1) above we have

We will now rewrite this by replacing by different dummy variables of integration so that we can write the product of the two integrals as a double integral. We then have

We now make the change of variables in the inner integral in (19), i.e., the integral with respect to

, so that

is treated as fixed. Then

,

, and when

we have

, while when

we have

. Then (19) becomes

We will now change the order of integration using the following diagrams to interpret what is going on in (20):

From the first diagram, we see that the double integral in (20) is over the area to the right of the diagonal line. Within a given strip of width

, the

integral adds up little area elements from the line

to

, then the

integral sums over the horizontal strips from

to

, covering the whole infinite area to the right of the diagonal line. However, we can obtain exactly the same result by considering a vertical strip of width

as shown in the second diagram. Changing the order of integration and integrating with respect to

first, then within the given strip of width

, the

integral adds up little area elements from

to the line

, and then the

integral sums over the vertical strips from

to

. In doing things this way round, we are working with the double integral

where the last step follows from the definition of a Laplace transform in (1) above. As per the construction in the diagrams, the two integrals (20) and (21) must be the same, so the convolution theorem in (17) is proved. The proof is useful in showing how a double infinite integral can be converted into a double integral in which only one of the integrals is improper, and vice versa. I have come across the need for this technique in different contexts.