I record here an experience of manually calculating a Fast Fourier Transform (FFT). Carrying out the computations by hand turned out to be relatively straightforward and quite instructive. A number of different FFT algorithms have been developed and the underlying equations are provided in numerous journal articles and books. I chose to calculate an eight-point (real-valued) FFT using the equations and approach discussed in the book Approximation Theory and Methods by M. J. D. Powell.

The classical Fourier analysis problem is to express a periodic function of period

in the form

In the context of approximation theory, the above Fourier series is truncated so that some is the highest value of

for which at least one of

or

is non-zero, i.e.,

We then regard as a trigonometric polynomial of degree

which approximates the function

(this approximation can be shown to minimise a least squares distance function).

The task is to find formulas for the coefficients and

and this is achieved using the following formulas for the average values over a period of

,

and

respectively:

Then to find the value of the coefficient in the Fourier series expansion of

we take the average value of the series by integrating on

term by term. We get

with all the other terms on the right-hand side equal to zero because they can all be regarded as integrals of or of

with

and

(i.e.,

). We are thus left with

This is the formula for calculating the coefficient in the Fourier series expansion of a periodic function

. From then on, to find

for

, we multiply both sides of the generic Fourier series expansion by

and again find the average value of each term to get

Analogously, to obtain the formula for , we multiply both sides of the generic Fourier series expansion by

and take average values. We find

This classical setup assumes that the values of the function are known for all

in the interval

. When this is not the case and we only have the values of

for a discrete set of points in the interval

, we need to use a discretised form of Fourier series approximation. Powell approaches this in Section 13.3 of his book as follows:

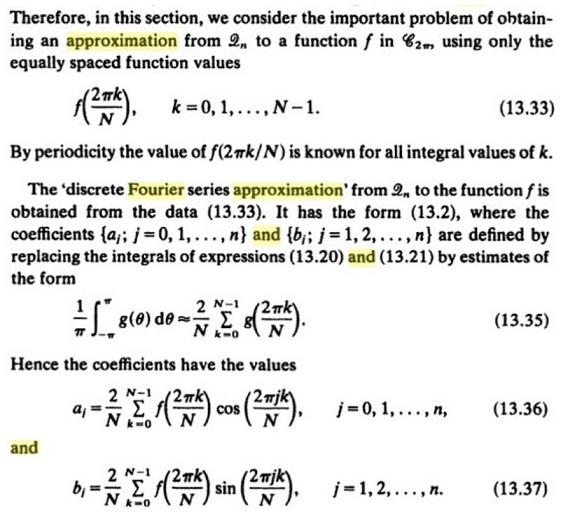

Therefore the classical formulas

and

are replaced by formulas (13.36) and (13.37) in the excerpt above. To illustrate how these formulas work in a concrete example, suppose the problem is to to obtain an approximation of a function by a trigonometric polynomial of degree

given only the four function values

,

,

and

. Thus, we need to obtain an approximation to

of the form

Setting , we use formulas (13.36) and (13.37) to evaluate the coefficients

,

,

,

and

as follows:

Therefore the required approximation is

The fast Fourier transform is designed to speed up the calculations in discrete Fourier series approximations of the above kind in cases when is large. Powell discusses this in Section 13.4 of his book as follows:

Each iteration of the FFT process depends on the value of the iteration variable , which initially is set at 1. In each subsequent iteration, the value of

is set at twice the previous value, so in the second iteration we have

, in the third iteration we have

, in the fourth iteration we have

and so on. This continues until the value of the iteration variable reaches

(which in this particular FFT approach is required to be a power of

).

At the start of the first iteration we set and

. Formula (13.46) then reduces to

and formula (13.47) reduces to

where for each the values of

are the numbers in the set

So, in the first iteration we use the above formulas to generate values of

and

. We then use formulas (13.50) to obtain the numbers

and

. We get

Thus, the numbers and

are exactly the same as the numbers

and

in this first iteration. At this point we are ready to begin the second iteration.

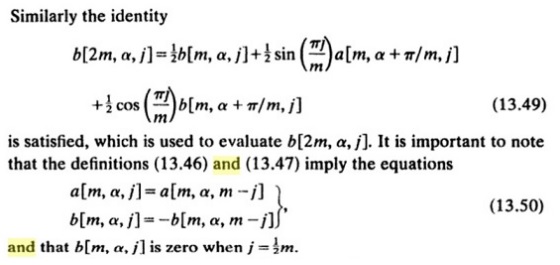

For the second iteration we double the iteration variable and use the results from the first iteration to compute the numbers and

for

using formulas (13.48) and (13.49). The variable

runs from

to

in this second iteration. We then use formulas (13.50) to obtain the numbers

and

for

and at this point we are ready to begin the third iteration.

For the third iteration we double the iteration variable again (so ) and use the results from the second iteration to compute the numbers

and

for

using formulas (13.48) and (13.49). The variable

runs from

to

in this third iteration. We then use formulas (13.50) to obtain the numbers

and

for

and at this point we are ready to begin the fourth iteration.

For the fourth iteration we double the iteration variable again (so ) and use the results from the third iteration to compute the numbers

and

for

using formulas (13.48) and (13.49). The variable

runs from

to

in this fourth iteration. We then use formulas (13.50) to obtain the numbers

and

for

and at this point we are ready to begin the fifth iteration.

Thus, we see that at the end of each iteration the numbers and

are known, where

takes all the integer values in

and the variable

runs from

to

. The iterations continue in this fashion until we arrive at the numbers

and

for

and these provide the required coefficients for the approximation.

To illustrate how all of this works in a concrete example, I will solve a problem at the end of this chapter of Powell’s book. The problem reads as follows:

Therefore, we need to obtain an approximation to the data of the form

Applying the iterative process described above with , we begin by setting

,

and

in formulas (13.46) and (13.47). Formula (13.46) reduces to

so we get the eight values

and formula (13.47) reduces to

which gives us

Next we calculate the numbers and

using equations (13.50), which tell us that

Thus, the numbers and

are exactly the same as the numbers

and

in this first iteration. Writing them out explicitly:

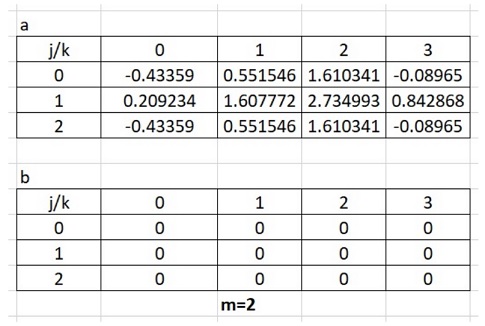

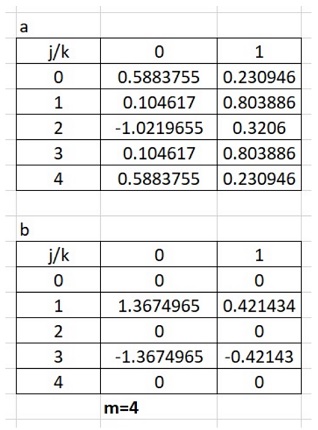

The above results can be summarised in a table for convenience:

We are now ready to begin the second iteration. The iteration variable becomes and we will have

,

. We compute the numbers

,

,

and

using formulas (13.48) and (13.49). We get the formulas

These then give us the values

Next we calculate the numbers and

using equations (13.50), which tell us that

Thus, the numbers and

are exactly the same as the numbers

and

in the second iteration. Writing them out explicitly:

The above results are summarised in the following table for convenience:

We are now ready to begin the third iteration. The iteration variable becomes and we will have

,

. We compute the numbers

,

,

,

,

and

using formulas (13.48) and (13.49). We get the formulas

These then give us the values

Next we calculate the numbers ,

,

and

using equations (13.50), which tell us that

Thus, we can use the previously computed values for and

in the third iteration to get these. Writing them out explicitly:

The above results are summarised in the following table:

We are now ready to begin the fourth (and final) iteration. The iteration variable becomes and we have

,

. We compute the numbers

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

,

and

using formulas (13.48) and (13.49). We get

The above results are summarised in the following table:

The required approximation is then

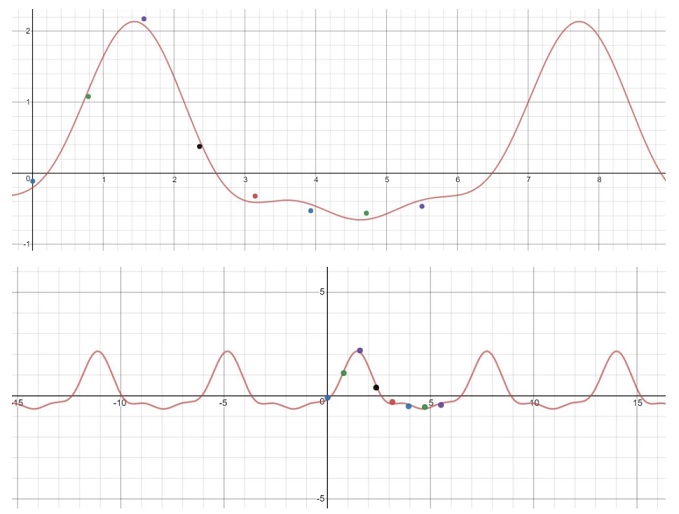

The graph of is plotted in the figures below for comparison with the initial data (the second figure shows more of the periodic pattern):