For the purposes of a lecture on computational applied mathematics, I wanted to illustrate the solution of nonlinear simultaneous equations by first employing contour plots or grid search techniques to find approximate solutions before using these approximate solutions as starting values for more accurate quasi-newton root finding methods. I decided to illustrate these techniques using the pairs of energy conservation and momentum conservation equations that arise when modelling elastic collisions in both Newtonian and relativistic physics. I was intrigued by some similarities in the contour plots I obtained for the two cases and want to record these results here.

For the Newtonian case, I considered the following problem: A ball of mass kg moving with initial velocity

m/s collides elastically with a ball of mass

kg moving with initial velocity

m/s. Assume all motion occurs in one dimension. Calculate the final velocities

and

of the

kg ball and the

kg ball respectively after the collision.

In such an elastic collision, both energy and momentum are conserved, so the following equations must hold respectively:

We need to solve these simultaneously for and

.

For the relativistic case, I considered the following problem: A -meson of rest energy

= 139.6 MeV moving with initial velocity

= 0.9 collides elastically with a proton of rest energy

= 938.2 MeV and with initial velocity

= 0.1. Assume all motion occurs in one dimension, and note that in a relativistic elastic collision the rest masses are unchanged after the collision. Calculate the final velocities

and

of the

-meson and the proton respectively after the collision.

We again note that in an elastic collision both energy and momentum are conserved, so the following relativistic equations must hold respectively:

We need to solve these simultaneously for and

. To use the data given in the problem, we need to manipulate the second equation to obtain velocities relative to the speed of light

and rest energies in the numerator (this manipulation effectively multiplies the momentum conservation equation through by

, but this does not affect the results since the extra factor of

appears on both sides of the equation and therefore cancels):

We can then obtain contour plots of the relativistic energy and momentum conservation equations using the data in the problem and with the equations rearranged to equal zero:

We need to solve these simultaneously for and

.

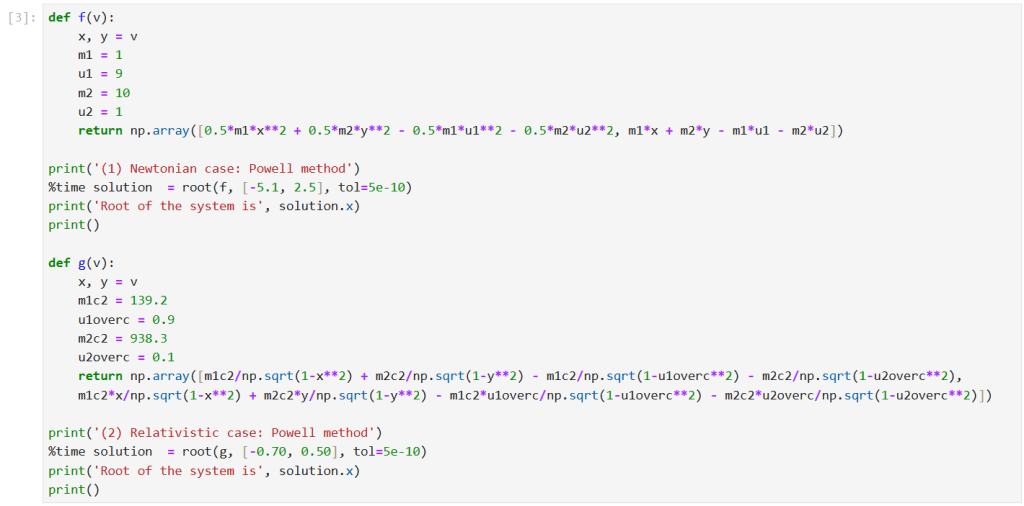

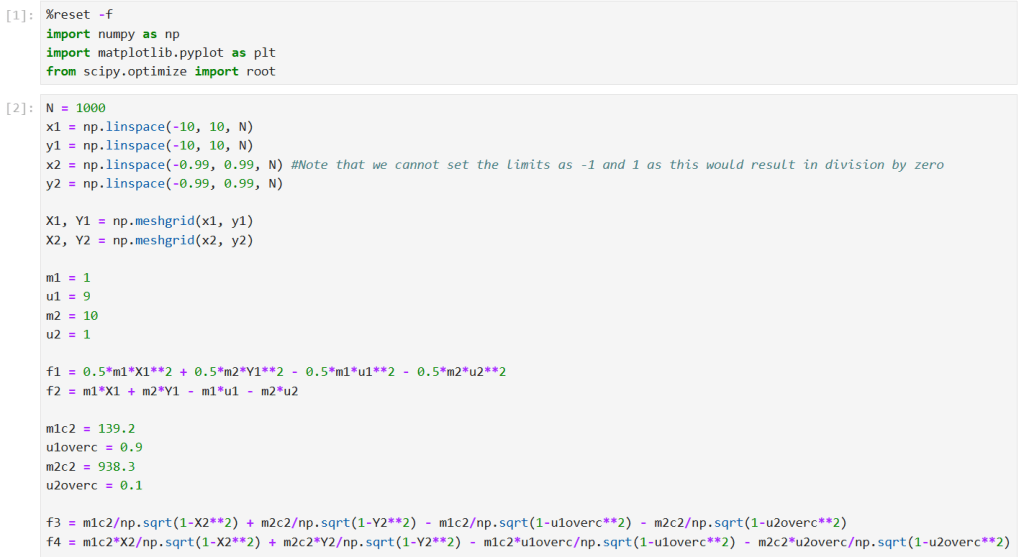

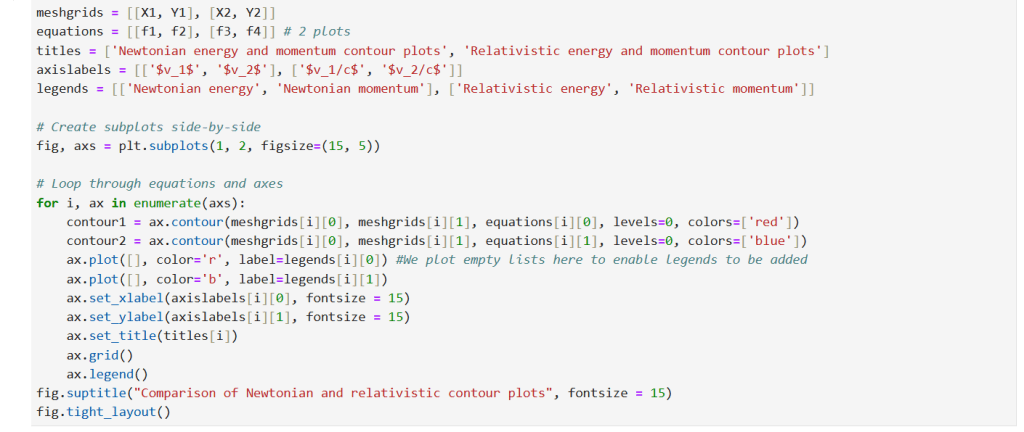

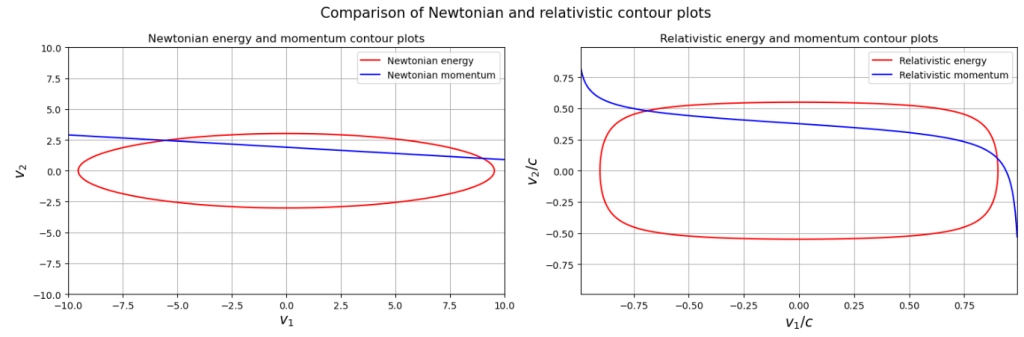

I used the Axes object-oriented interface in Python with the data given in the problems to obtain contour plots of these pairs of equations for each of the Newtonian and relativistic cases side by side. The Python code and results are as follows.

So, both systems have two roots, a trivial one which involves setting the final velocities equal to the initial velocities, and a nontrivial root. For the Newtonian case, the nontrivial root is near , while for the relativistic case the nontrivial root is near

.

For the Newtonian case, it was not too surprising to see that the energy equation produced a contour which is a closed loop (actually, an ellipse) while the momentum equation produced a contour which is an open curve (actually, a straight line). The reason for this difference is that the kinetic energy of each ball is bounded below by zero and above by the total energy of the system (determined by the initial conditions), so the closed energy contour arises as a result of the total energy being distributed continuously between the balls subject to these bounds, with a symmetry between negative and positive velocities arising due to the quadratic functional form of Newtonian kinetic energy. In contrast, the velocities in the Newtonian momentum equation are free to vary from minus infinity to infinity as long as the total momentum (also determined by the initial conditions) is conserved, and the velocities also appear linearly in the momentum equation so the contour for momentum is unable to ‘close’ and in fact is a straight line extending indefinitely in both directions.

What intrigued me is that the relativistic case also produced a closed loop for the energy contour and an open curve for the momentum contour. The energy contour is a closed loop for reasons which are similar to those of the Newtonian case. In the relativistic case, the energy of each particle is bounded below by its rest energy (given by Einstein’s famous formula ) and bounded above by the total energy of the system (determined by the initial conditions) minus the rest energy of the other particle, so the closed energy contour again arises as a result of the total energy being distributed continuously between the particles subject to these bounds, and due to a symmetry between negative and positive velocities arising due to the quadratic form of the velocity term in the Lorentz factor. In the case of momentum, however, even though relativistic velocities are bounded by the speed of light

, we still get an open curve for the momentum contour (though not one that extends indefinitely) because velocity appears linearly in the numerator of the relativistic momentum terms so the contour for momentum is still unable to ‘close’ in this case.

To find the nontrivial roots accurately, we choose the starting value for the Newtonian case and the starting value

for the relativistic case. We can employ the general-purpose multidimensional root-finding function root() from the Python library scipy, which allows us to select from a range of different methods (Newton-Raphson, Broyden, Powell and Newton-Krylov). In the following code I use Powell’s method.