For the purposes of a lecture, I wanted a very straightforward mathematical setup leading quickly from a simple random walk to the Wiener process and also to the associated diffusion equation for the Gaussian probability density function (pdf) of the Wiener process. I wanted something simpler than the approach I recorded in a previous post for passing from a random walk to Brownian motion with drift. I found that the straightforward approach below worked well in my lecture and wanted to record it here.

The key thing I wanted to convey with the random walk model is how the jumps at each step have to be of a size exactly equal to the square root of the step length in order for the limiting process to yield a variance for the stochastic process that is finite at the limit but not zero. To this end, suppose we have an interval of time and we divide it into

subintervals of length

, so that

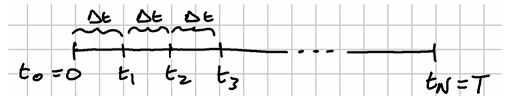

The situation is illustrated in the following sketch:

For each time step , define the simple random walk

where for we have

The mean and variance of are easily calculated as

and

The recurrence relation in (2) represents a progression through a simple random walk tree starting at , as illustrated in the following picture:

Running the recurrence relation with back substitution we obtain

where . The mean and variance of

are again easily calculated as

and

This final expression for the variance is the one I wanted to get to as quickly as possible. It shows that for the variance to remain finite but not zero as we pass to the limit , it must be the case that

. From (7) we then obtain

which is the characteristic variance of a Wiener process increment over a time interval . Any other choice of

would lead to the variance of the random walk either exploding (if

) or flatlining (if

), rather than settling into a Wiener process as

.

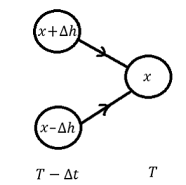

Next, I wanted to show how the Gaussian pdf of the Wiener process follows immediately from the above random walk structure (without any need to appeal to the central limit theorem for the sum in (5)). Over an interval of time to

, the simple random walk underlying the Wiener process can reach a point

by increasing from the point

or by decreasing from the point

, as illustrated in the following picture:

Each of these has a probability of , so the probability density function

we are looking for must satisfy

We now Taylor-expand each of the terms on the right-hand side about to obtain

and similarly

Note that we will be setting equal to

and letting

, so we do not need to include any of the higher-order

or

terms in these Taylor expansions. Substituting (10) and (11) into (9) and setting

gives

which simplifies to

This is the diffusion equation for the standard Wiener process which has as its solution the Gaussian probability density function

This can easily be confirmed by direct substitution (cf. my previous post where I play with this).