Quantum mechanical models in three dimensions and involving many particles, etc., use a formalism which is largely based on some key mathematical modelling ideas pertaining to single particle systems. These mathematical modelling ideas are principally designed to tell us what sets of values we are `allowed’ to observe when we measure some aspect of a quantum system, and with what probabilities we can expect to observe particular values from these sets. For quick reference, I wanted to have a relatively brief and coherent overview of these key mathematical ideas and have written the present note for this purpose. Dirac notation is used throughout.

Quantum particle in a ring

To start with, suppose all we know is that a quantum particle in a closed ring of length  has a given linear momentum

has a given linear momentum  when an observation of its position is made. The result of the observation is that the particle will be found at some point

when an observation of its position is made. The result of the observation is that the particle will be found at some point  lying in a small interval of length

lying in a small interval of length  on the closed ring. We assume that the radius of the ring is sufficiently large to make angular momentum considerations negligible. De Broglie tells us that the linear momentum of the quantum particle must be associated with a wavelength

on the closed ring. We assume that the radius of the ring is sufficiently large to make angular momentum considerations negligible. De Broglie tells us that the linear momentum of the quantum particle must be associated with a wavelength  of some wave function

of some wave function  according to the rule

according to the rule

where  is Planck’s constant. (There is also a fundamental equation

is Planck’s constant. (There is also a fundamental equation  linking the energy of a quantum particle to the frequency of a wave function. This will be introduced later in connection with modelling time evolution in quantum mechanics). Somewhat surprisingly at first sight, this is all the information we need to deduce a precise functional form for the wave function

linking the energy of a quantum particle to the frequency of a wave function. This will be introduced later in connection with modelling time evolution in quantum mechanics). Somewhat surprisingly at first sight, this is all the information we need to deduce a precise functional form for the wave function  as well as the allowed spectrum of momenta for the particle. (Note that

as well as the allowed spectrum of momenta for the particle. (Note that  gives the probability that a particle with momentum

gives the probability that a particle with momentum  will be found at a position

will be found at a position  lying in a small interval of length

lying in a small interval of length  on the closed ring. This probability distribution can be observed through experiment, while

on the closed ring. This probability distribution can be observed through experiment, while  itself is unobservable directly. We refer to

itself is unobservable directly. We refer to  as a quantum mechanical probability amplitude in this connection).

as a quantum mechanical probability amplitude in this connection).

First, we imagine what the position wave function  must look like as a Fourier series. Since only a single wavelength is involved in this particular setup,

must look like as a Fourier series. Since only a single wavelength is involved in this particular setup,  must be a pure wave, i.e., the exponential form of its Fourier series must consist of a single term, so we must have

must be a pure wave, i.e., the exponential form of its Fourier series must consist of a single term, so we must have

for some  that still remains to be calculated, where

that still remains to be calculated, where  is the wave number

is the wave number

Combining (1) and (3), we can write de Broglie’s linear momentum formula as

where  is the reduced Planck’s constant. We can then rewrite the above wave function to explicitly incorporate momentum as

is the reduced Planck’s constant. We can then rewrite the above wave function to explicitly incorporate momentum as

An assumption called the certainty condition in quantum mechanics, or sometimes the square integrability condition or normalizability condition, is that the quantum particle must be found upon measurement to be located somewhere on the ring, so we must have

(This requires quantum mechanics to take place in a Hilbert space of square-integrable functions, as discussed further below). Substituting our wave function so far into this then gives  , so we can write the full position wave function as

, so we can write the full position wave function as

Second, to deduce the permitted spectrum of momenta, we use the fact that the position wave function for a quantum particle in a ring must be periodic with period  , so we must have

, so we must have

Therefore

which implies

for  , and therefore the permitted spectrum of momenta for this setup is given by

, and therefore the permitted spectrum of momenta for this setup is given by

It is impossible for this quantum particle to have a momentum  that does not belong to this particular discrete spectrum.

that does not belong to this particular discrete spectrum.

In our one-dimensional quantum particle in a ring system, a measurement result that is nondegenerate uniquely defines a state of the system, denoted by a ket  in Dirac notation, e.g.,

in Dirac notation, e.g.,  for a momentum measurement or

for a momentum measurement or  for a position measurement. Formally, as outlined below, these kets are vectors in a Hilbert space. In contrast, a degenerate measurement is a measurement that cannot uniquely define a state of the system, i.e., it is consistent with more than a single state and is thus regarded as a superposition of states. As an example, the energy

for a position measurement. Formally, as outlined below, these kets are vectors in a Hilbert space. In contrast, a degenerate measurement is a measurement that cannot uniquely define a state of the system, i.e., it is consistent with more than a single state and is thus regarded as a superposition of states. As an example, the energy  of our particle in a ring system is degenerate because it is a quadratic function of momentum,

of our particle in a ring system is degenerate because it is a quadratic function of momentum,  , and there is nothing in the model to prevent the momentum being negative. Thus, the same value of

, and there is nothing in the model to prevent the momentum being negative. Thus, the same value of  can correspond to a momentum state

can correspond to a momentum state  or a momentum state

or a momentum state  , so the label

, so the label  cannot by itself be used to uniquely define a state

cannot by itself be used to uniquely define a state  here.

here.

An event is a measurement finding for a system when it is in a known, i.e., pre-prepared, state. For example, we can measure the position  for our system when we know the quantum particle in the ring has been prepared to have momentum state

for our system when we know the quantum particle in the ring has been prepared to have momentum state  . In quantum mechanics, all such events have probability amplitudes with the property that their absolute value squared gives a probability density for the event, as mentioned above. In this case, as mentioned earlier, the probability amplitude for the position measurement is

. In quantum mechanics, all such events have probability amplitudes with the property that their absolute value squared gives a probability density for the event, as mentioned above. In this case, as mentioned earlier, the probability amplitude for the position measurement is  in Dirac notation, with

in Dirac notation, with  . Note that there is an implicit assumption that the measurement of position occurs instantaneously after the quantum system has been prepared in its initial momentum state, i.e., there should not have been enough time for the system to evolve away from its pre-prepared momentum state before position is measured. This implicit assumption applies to all quantum events. Also note that the famous Dirac delta function in the continuous case (and the Kronecker delta function in the discrete case) arise by considering self-space events, i.e., performing the same measurement twice in rapid succession. For example, suppose the quantum particle is known to be in position state

. Note that there is an implicit assumption that the measurement of position occurs instantaneously after the quantum system has been prepared in its initial momentum state, i.e., there should not have been enough time for the system to evolve away from its pre-prepared momentum state before position is measured. This implicit assumption applies to all quantum events. Also note that the famous Dirac delta function in the continuous case (and the Kronecker delta function in the discrete case) arise by considering self-space events, i.e., performing the same measurement twice in rapid succession. For example, suppose the quantum particle is known to be in position state  and then a second measurement of position is quickly made. The measurement space in this case is continuous and the self-space probability amplitude

and then a second measurement of position is quickly made. The measurement space in this case is continuous and the self-space probability amplitude  is given by the Dirac delta function

is given by the Dirac delta function

which is such that  for

for  , while

, while  for

for  in such a way that

in such a way that  , and which famously also has as its defining property the integral equation

, and which famously also has as its defining property the integral equation

In the case of repeated measurements of momentum, which has a discrete measurement space for the quantum particle in a ring model, the corresponding self-space probability amplitude would be given by the Kronecker delta

which is such that  if

if  , and

, and  if

if  . The Dirac delta function can be thought of as the continuous measurement space analogue of the Kronecker delta for discrete spaces.

. The Dirac delta function can be thought of as the continuous measurement space analogue of the Kronecker delta for discrete spaces.

The abstract measurement space consisting of the spectrum of all possible results you can get from a measurement is a Hilbert space, i.e., a complex inner product space which is also a complete metric space with regard to the distance function induced by the inner product. The state of a physical system is treated as a vector in such a Hilbert space. There is a Hilbert space containing all the possible position and momentum states above, for example, and the probability amplitudes  are formally the inner products of the two state vectors

are formally the inner products of the two state vectors  and

and  in this Hilbert space. A necessary and sufficient condition for these inner products to exist is that the functions involved are square-integrable. The completeness of these measurement spaces means that each can act as a basis, i.e., a ‘language’, in terms of which other states can be represented. Thus, we can regard the probability amplitude

in this Hilbert space. A necessary and sufficient condition for these inner products to exist is that the functions involved are square-integrable. The completeness of these measurement spaces means that each can act as a basis, i.e., a ‘language’, in terms of which other states can be represented. Thus, we can regard the probability amplitude  as the projection of state

as the projection of state  on

on  -space, or the momentum state

-space, or the momentum state  expressed in the language of

expressed in the language of  , or simply the state

, or simply the state  expressed as a function of

expressed as a function of  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  can be interpreted as the position state

can be interpreted as the position state  expressed in the language of

expressed in the language of  . A key axiom of quantum mechanics is that

. A key axiom of quantum mechanics is that  and

and  are related via complex conjugation:

are related via complex conjugation:

So, for example, given  as defined in (7) above, we can immediately deduce that

as defined in (7) above, we can immediately deduce that

(But remember that these probability amplitudes are never directly observable. Only the associated probability distributions are observable experimentally).

We can use this idea of measurement spaces acting as language spaces (or, more formally, basis sets) to express one state as a superposition of other states. For example, a hypothetical state  can be experimentally resolved into momentum state components, expressed mathematically as the superposition

can be experimentally resolved into momentum state components, expressed mathematically as the superposition

This is a discrete sum because recall that, for the quantum particle in a ring model, the measurement space for momentum is discrete. On the right-hand side, each  is a pure momentum state, and the bra-ket

is a pure momentum state, and the bra-ket  is the weight attached to this pure momentum state in the superposition. The same state

is the weight attached to this pure momentum state in the superposition. The same state  can equally well be perceived as a superposition of position states:

can equally well be perceived as a superposition of position states:

The summation here is to be implemented as an integral since the measurement space for position is continuous for the quantum particle in a ring model. Thus, we can write (14) in integral form as

Notice how the delta function definition of the self-space amplitude,  , now arises in this integral when computing the coefficients of the expansion of

, now arises in this integral when computing the coefficients of the expansion of  in terms of the continuous position basis:

in terms of the continuous position basis:

Thus, the position space wave functions  , evaluated at particular values of

, evaluated at particular values of  , are just the coefficients of a state

, are just the coefficients of a state  (belonging to Hilbert space) in a superposition using a continuous position basis.

(belonging to Hilbert space) in a superposition using a continuous position basis.

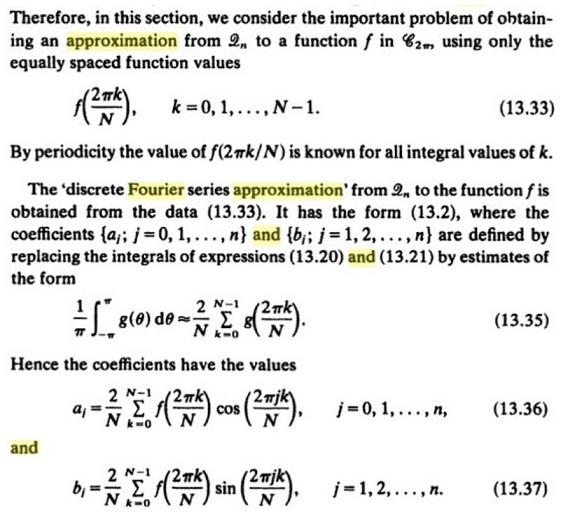

It is useful to bear in mind that these superposition equations are analogous to how a periodic function  can be expanded in a Fourier series. We are using the same kinds of mathematical structures and arguments in defining the superpositions above.

can be expanded in a Fourier series. We are using the same kinds of mathematical structures and arguments in defining the superpositions above.

Both of the superposition equations above are special cases of a general rule called the completeness theorem or superposition theorem, which can be expressed mathematically in Dirac notation as

The ket  on the left-hand side of this equation is a pure

on the left-hand side of this equation is a pure  -state. The bra

-state. The bra  can be regarded here as an operator that, when it is applied to any state

can be regarded here as an operator that, when it is applied to any state  , gives the weight attached to that pure

, gives the weight attached to that pure  -state in the superposition for

-state in the superposition for  :

:

In this last equation, it is as if we are multiplying  on the right-hand side by 1 to get

on the right-hand side by 1 to get  again on the left-hand side, so we represent this situation as in equation (15) above.

again on the left-hand side, so we represent this situation as in equation (15) above.

Measuring an observable for our quantum system, assuming the system has been prepared so that it is in a known state when the measurement takes place, is modelled mathematically as applying a suitable operator to the prepared state ket. If an operator  operates on a state ket

operates on a state ket  , another new state ket is produced denoted by

, another new state ket is produced denoted by  . For each such operator

. For each such operator  , there must be a rule or instruction which tells us what is produced when the ket undergoes the operation. This rule must itself be given in some language, e.g., the representation of

, there must be a rule or instruction which tells us what is produced when the ket undergoes the operation. This rule must itself be given in some language, e.g., the representation of  in

in  -space is denoted

-space is denoted  , and in

, and in  -space is denoted

-space is denoted  . An important example is the operator

. An important example is the operator  whose rule in

whose rule in  -space is take the derivative with respect to x. Therefore, in Dirac notation:

-space is take the derivative with respect to x. Therefore, in Dirac notation:

This equation can be applied to any ket, so for example

In the same way that a state has an existence which is independent of the language used to represent it, so too may operators be expressed in different languages. For example, we can convert an instruction  in

in  -language to an instruction

-language to an instruction  in

in  -language by using a ket-bra sum

-language by using a ket-bra sum  . We get

. We get

No specific state  is involved here, so we can write the general language-translation-rule as

is involved here, so we can write the general language-translation-rule as

To give an example of implementing this in practice, recall that for our quantum particle in a ring system we have

Therefore, the conversion represented by (19) can be written in conventional notation as

Integrating the right-hand side by parts, we find it equals

Therefore,

Since  is arbitrary, the general rule is

is arbitrary, the general rule is

The operators that represent measurement of observables in quantum mechanics are linear and hermitian. (A hermitian matrix is the complex analogue of a symmetric matrix. It is equal to its own conjugate transpose. Another type of matrix which arises frequently in quantum mechanics is a unitary matrix. This is the complex analogue of an orthogonal matrix, the latter having the property that the transpose matrix is the inverse. In the case of a unitary matrix, the complex conjugate transpose is the inverse. Hermitian operators are usually related to the measurement of observables in quantum mechanics, whereas unitary operators are related to carrying out processes such as translations of quantum states in space and time. We need to extend the symmetric and orthogonal properties of ordinary matrices to include complex conjugation in the definition of hermitian and unitary matrices to cater for the fact that quantum mechanics involves complex numbers, e.g., in the unitary matrix case, simply transposing a complex matrix and multiplying by the original matrix would in general produce another complex matrix rather than an identity matrix, without the complex conjugation step). As per Sturm-Liouville theory, hermitian operators have the property that their eigenvalues are real and form complete measurement spaces, i.e., they represent the entire spectrum of values that can be observed when a measurement is made. It is important to understand, however, that these eigenvalues are only revealed when the operator is applied to its particular home measurement space, formally called its eigenspace. Each operator is defined in terms of a particular instruction (telling us what the operator does) and in terms of the set of eigenvalues it gives rise to when it is applied to its particular eigenspace. The effect of applying an operator to a ket in its eigenspace will be to produce the same ket multiplied by an eigenvalue of the operator. The kets for which this happens are the eigenkets of the operator. For example, based on the result in (22) above, define a new operator  as

as

Then on the basis of (22), we immediately deduce that

This is the bra form of the eigenvalue equation for  , meaning that in

, meaning that in  -language, which is the language of the eigenspace of

-language, which is the language of the eigenspace of  , the effect of

, the effect of  is to multiply any state it operates on by a number

is to multiply any state it operates on by a number  . We can equivalently state the eigenvalue equation in ket form:

. We can equivalently state the eigenvalue equation in ket form:

This is saying that the effect of  on its eigenket is to produce a number times the same eigenket, no matter what language the instruction for

on its eigenket is to produce a number times the same eigenket, no matter what language the instruction for  is expressed in. The two forms (24) and (25) are equivalent, and both mean that the operator

is expressed in. The two forms (24) and (25) are equivalent, and both mean that the operator  produces the spectrum of momenta for the quantum particle in a ring model, and the eigenkets of

produces the spectrum of momenta for the quantum particle in a ring model, and the eigenkets of  are

are  . We say that the

. We say that the  -space kets

-space kets  are eigenstates of

are eigenstates of  with eigenvalues

with eigenvalues  . Notice that when the operator

. Notice that when the operator  is expressed in

is expressed in  -language instead of

-language instead of  -language, we do not get a proper eigenvalue equation (see (18) above). Therefore,

-language, we do not get a proper eigenvalue equation (see (18) above). Therefore,  -space is not the eigenspace of

-space is not the eigenspace of  . However, when the operator

. However, when the operator  is expressed in

is expressed in  -language, we do get a proper eigenvalue equation (equation (22) above), so

-language, we do get a proper eigenvalue equation (equation (22) above), so  -space is the eigenspace for

-space is the eigenspace for  .

.

Similarly, since position is a measurable quantity for the quantum particle in a ring, there is a position operator  which generates a position measurement space, just as

which generates a position measurement space, just as  generates momentum measurement space. The eigenvalue equation for

generates momentum measurement space. The eigenvalue equation for  is simply

is simply

Note that each of  and

and  can be expressed in the language of the other’s space. Expressing

can be expressed in the language of the other’s space. Expressing  in

in  -language, we find

-language, we find

(Proof:  ). Similarly, expressing

). Similarly, expressing  in

in  -language we get

-language we get

(Proof:  ). In each case, we are not using the correct eigenspace for the operator, so the equations we get are not in the form of proper eigenvalue equations. However, we can check that (27) and (28) are correct by seeing if they do produce proper eigenvalue equations when applied to the correct kets. When applied to the ket

). In each case, we are not using the correct eigenspace for the operator, so the equations we get are not in the form of proper eigenvalue equations. However, we can check that (27) and (28) are correct by seeing if they do produce proper eigenvalue equations when applied to the correct kets. When applied to the ket  , equation (27) must produce the proper eigenvalue equation

, equation (27) must produce the proper eigenvalue equation

Therefore we need to confirm that

but this result is immediate when we substitute (12) into each side of (30). Similarly, when applied to the ket  , equation (28) must produce the proper eigenvalue equation

, equation (28) must produce the proper eigenvalue equation

Therefore we need to confirm that

but this is again immediate when we substitute (7) into each side of (32).

Another interesting thing to observe here is that we can reverse this argument and derive the form of the probability amplitude  as a function of

as a function of  from (32), interpreted as a differential equation. We can regard (32) as the the eigenvalue equation in (25) above, but expressed in the language of

from (32), interpreted as a differential equation. We can regard (32) as the the eigenvalue equation in (25) above, but expressed in the language of  (i.e., the differential equation in (32) is obtained by introducing the bra

(i.e., the differential equation in (32) is obtained by introducing the bra  in (25) above, yielding

in (25) above, yielding  ). The solution to (32) is precisely the form of

). The solution to (32) is precisely the form of  given in (7) above, with the constant coming from the normalization condition

given in (7) above, with the constant coming from the normalization condition  as before.

as before.

In addition to position and momentum operators  and

and  , energy is also an observable, so it must have an operator that generates the spectrum of measurable energies. This is the Hamiltonian operator, which for a quantum particle in a ring model has the form

, energy is also an observable, so it must have an operator that generates the spectrum of measurable energies. This is the Hamiltonian operator, which for a quantum particle in a ring model has the form

(There is no potential energy in our simple model system, so no function of  in the Hamiltonian). Note that the form of the operator

in the Hamiltonian). Note that the form of the operator  is the same as the form of the classical kinetic energy function

is the same as the form of the classical kinetic energy function  . In the quantum case, the eigenvalues of

. In the quantum case, the eigenvalues of  are precisely

are precisely  . Remarkably, a simple rule that works for finding quantum mechanical operators corresponding to classical observables is to put hats on the observables in algebraic relations between classical observables. This is how we can get

. Remarkably, a simple rule that works for finding quantum mechanical operators corresponding to classical observables is to put hats on the observables in algebraic relations between classical observables. This is how we can get  from

from  . As another example, we could in principle obtain a quantum velocity operator as

. As another example, we could in principle obtain a quantum velocity operator as  .

.

Having the form of the Hamiltonian operator  , we can now find its eigenvalues from the eigenvalue problem that generates them:

, we can now find its eigenvalues from the eigenvalue problem that generates them:

This is actually the general form of the famous time-independent Schrödinger equation. Casting this equation into  -space, we can solve for the probability amplitudes

-space, we can solve for the probability amplitudes  :

:

This is a simple second-order linear differential equation with general solution

From the fact that this wave function must be single-valued for our quantum particle in a ring, we deduce

for  . Remember, however, that there is degeneracy in

. Remember, however, that there is degeneracy in  for the quantum particle in a ring model: there is nothing to prevent there being two possible

for the quantum particle in a ring model: there is nothing to prevent there being two possible  -states (one positive, one negative) for each value of

-states (one positive, one negative) for each value of  .

.

Quantum particle on an infinite line

Suppose we modify the previous model by allowing the radius of the ring,  , to become infinitely large, so that the `track’ now effectively extends infinitely to the right and infinitely to the left of the starting point at zero. The quantum particle is then free to move anywhere on the real line, i.e., the position measurement space has become

, to become infinitely large, so that the `track’ now effectively extends infinitely to the right and infinitely to the left of the starting point at zero. The quantum particle is then free to move anywhere on the real line, i.e., the position measurement space has become  . For such a quantum particle, momentum is no longer quantized (intuitively, this is because the probability amplitude periodicity constraint

. For such a quantum particle, momentum is no longer quantized (intuitively, this is because the probability amplitude periodicity constraint  is no longer relevant), so the momentum measurement space is now

is no longer relevant), so the momentum measurement space is now  . In this context, with both position and momentum being continuous measurement spaces, Fourier transforms arise naturally because they enable any function of

. In this context, with both position and momentum being continuous measurement spaces, Fourier transforms arise naturally because they enable any function of  over the domain

over the domain  , such as

, such as  , to be expanded as an integral in

, to be expanded as an integral in  over the same domain:

over the same domain:

where  is given by

is given by

We can use this Fourier transform relationship to obtain physically-realistic mathematical models of a quantum particle on an infinite line. As is well known, in order to obtain a well-behaved wave function representation of a free particle on an infinite line, i.e., a wave function that is square-integrable, it is necessary to construct a superposition of pure waves incorporating a continuous range of wave numbers  . This wave packet approach then naturally gives rise to discussions relating to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Before considering this, however, it is interesting to note that we can also derive a pseudo-normalized pure wave form for the wave function

. This wave packet approach then naturally gives rise to discussions relating to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Before considering this, however, it is interesting to note that we can also derive a pseudo-normalized pure wave form for the wave function  in the case of a quantum particle on an infinite line, somewhat analogous to the pure wave form in the previous section. To do this, we will first obtain a representation of the Dirac delta function using the above Fourier transform by letting

in the case of a quantum particle on an infinite line, somewhat analogous to the pure wave form in the previous section. To do this, we will first obtain a representation of the Dirac delta function using the above Fourier transform by letting  . Putting this into (38) gives

. Putting this into (38) gives

Then, putting this result into (37) gives us the following useful representation:

We will also observe that for any  , we have

, we have

(To see this, note first that  because

because  . Therefore, only the absolute value of

. Therefore, only the absolute value of  in

in  is relevant. We need to show that

is relevant. We need to show that  . In the integral on the left-hand side, make the change of variable

. In the integral on the left-hand side, make the change of variable  . Then

. Then  and

and  , and noting that

, and noting that  , i.e., both are functions of

, i.e., both are functions of  , we can write

, we can write  as required).

as required).

We now use this machinery to derive an explicit pure wave functional form for  . First, consider the self-space bra-ket

. First, consider the self-space bra-ket

where the final equality follows from (41). Using (40), reversing the roles of  and

and  there, we can write

there, we can write

![= \int_{-\infty}^{\infty} dx \big[\frac{1}{\sqrt{h}}\exp(-i k x)\big]\big[\frac{1}{\sqrt{h}} \exp(i K x) \big]\qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (43)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%3D+%5Cint_%7B-%5Cinfty%7D%5E%7B%5Cinfty%7D+dx+%5Cbig%5B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%5Csqrt%7Bh%7D%7D%5Cexp%28-i+k+x%29%5Cbig%5D%5Cbig%5B%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B%5Csqrt%7Bh%7D%7D+%5Cexp%28i+K+x%29+%5Cbig%5D%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2843%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

But we also have in Dirac notation

Comparing (43) and (44) we can immediately see that

The only difference between  here and in (7) above for the quantum particle in a ring case is that the normalization constant here is

here and in (7) above for the quantum particle in a ring case is that the normalization constant here is  instead of

instead of  . It is easily checked that (45) is in fact not square-integrable for the case of the quantum particle on an infinite line, i.e.,

. It is easily checked that (45) is in fact not square-integrable for the case of the quantum particle on an infinite line, i.e.,  is not an element of a Hilbert space in the conventional way here, since

is not an element of a Hilbert space in the conventional way here, since  . Instead, a kind of pseudo-normalization convention is being used in specifying the normalization constant in (45), called normalization to a Dirac delta function. From (43) (remembering that

. Instead, a kind of pseudo-normalization convention is being used in specifying the normalization constant in (45), called normalization to a Dirac delta function. From (43) (remembering that  ) we see that the normalization constant in (45) is giving us normalization to a Dirac delta function in the form

) we see that the normalization constant in (45) is giving us normalization to a Dirac delta function in the form

However, the non-square-integrable individual pure waves in (45) do not represent physically realizable states. To construct a square-integrable wave packet representation of a quantum particle on a line, we go back to the Fourier transform equation (37) above and regard it as a sum of pure waves over a continuous range of wave numbers  , with the amplitudes of these pure waves being modulated by the function

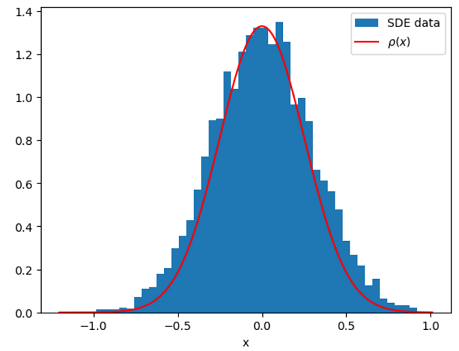

, with the amplitudes of these pure waves being modulated by the function  . A standard example is a Gaussian wave packet which we can obtain here by specifying

. A standard example is a Gaussian wave packet which we can obtain here by specifying

where  is some fixed wave number. Note that

is some fixed wave number. Note that  is the probability density function of a

is the probability density function of a  variable, i.e., up to a normalizing constant we get a Gaussian probability distribution for the wave number

variable, i.e., up to a normalizing constant we get a Gaussian probability distribution for the wave number  centered on

centered on  with standard deviation

with standard deviation  . Inserting this expression for

. Inserting this expression for  in (37) gives

in (37) gives

The integral here can be solved using straightforward changes of variables to give the result

This is a localized wave function and is square-integrable since  is the probability density function of a

is the probability density function of a  variable, i.e., we get a Gaussian probability distribution for the position

variable, i.e., we get a Gaussian probability distribution for the position  centered at zero and with standard deviation

centered at zero and with standard deviation  . (As a check, note that substituting this expression for

. (As a check, note that substituting this expression for  into (38) must give us the expression we used for

into (38) must give us the expression we used for  . Using the the result

. Using the the result

and the fact that  , we can substitute the expression for

, we can substitute the expression for  into (38) to get

into (38) to get

as required). Denoting the standard deviation of  by

by  and the standard deviation of

and the standard deviation of  by

by  , we have

, we have

But using  , we can write this as

, we can write this as

It can be shown that for anything other than a Gaussian wave packet we would find

and thus we obtain the famous Heisenberg uncertainty principle for position and momentum:

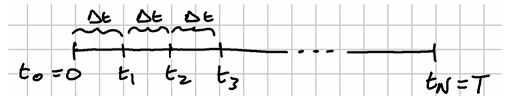

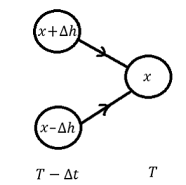

This wave packet model is a static one, i.e., the wave function  is time-independent. We can obtain a time-dependent wave function

is time-independent. We can obtain a time-dependent wave function  by multiplying the integrand in (37) by a quantum mechanical time evolution operator (the time evolution operator will be discussed below). Then, using the same

by multiplying the integrand in (37) by a quantum mechanical time evolution operator (the time evolution operator will be discussed below). Then, using the same  as in the static case and manipulating the integral in a similar manner as before, we find that

as in the static case and manipulating the integral in a similar manner as before, we find that  is again a localized Gaussian wave packet but now with the property that the standard deviation of the associated Gaussian probability distribution increases with time (i.e., the bell-shaped Gaussian probability distribution spreads out over time).

is again a localized Gaussian wave packet but now with the property that the standard deviation of the associated Gaussian probability distribution increases with time (i.e., the bell-shaped Gaussian probability distribution spreads out over time).

Quantum harmonic oscillator

To extend the model further, we now consider a quantum harmonic oscillator in which the position still has domain  . In this model, the momentum

. In this model, the momentum  is again no longer quantized but energy

is again no longer quantized but energy  remains quantized and is no longer a degenerate measurement. The approach is essentially to take the ideal classical harmonic oscillator’s Hamiltonian, convert it to a quantum mechanical Hamiltonian operator by `putting hats’ on the classical observables, and then use the operator to solve an eigenvalue problem.

remains quantized and is no longer a degenerate measurement. The approach is essentially to take the ideal classical harmonic oscillator’s Hamiltonian, convert it to a quantum mechanical Hamiltonian operator by `putting hats’ on the classical observables, and then use the operator to solve an eigenvalue problem.

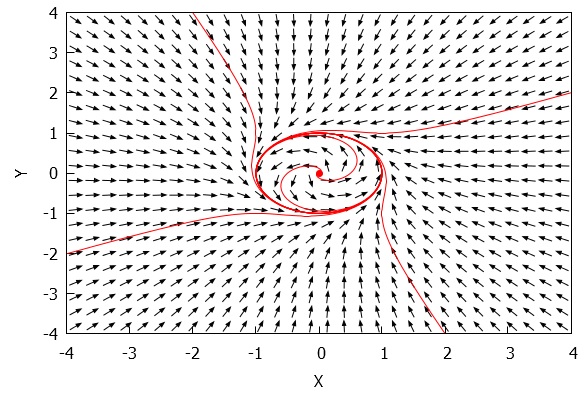

Recall that, in the ideal classical harmonic oscillator model, a particle of mass  attached to a spring with spring constant

attached to a spring with spring constant  is always pulled towards an equilibrium position by a Hooke’s law force

is always pulled towards an equilibrium position by a Hooke’s law force  . Newton’s second law

. Newton’s second law  then gives us a second-order differential equation

then gives us a second-order differential equation

with general solution

The angular frequency (or, equivalently, angular velocity – radians per second) is thus

and is usually referred to as the natural oscillation frequency of the harmonic oscillator.

The particle’s kinetic energy is  where

where  is the classical linear momentum, and, unlike the previous models, we now have a potential energy

is the classical linear momentum, and, unlike the previous models, we now have a potential energy  . (Recall that potential energy is the negative of work,

. (Recall that potential energy is the negative of work,  . For the classical harmonic oscillator, we have

. For the classical harmonic oscillator, we have  , so the potential energy is the negative of this). The classical Hamiltonian is then

, so the potential energy is the negative of this). The classical Hamiltonian is then

Using (49), we can write the corresponding quantum mechanical Hamiltonian operator as

As before, the position spectrum is generated by  and the momentum spectrum is generated by

and the momentum spectrum is generated by  . The energy spectrum is generated by

. The energy spectrum is generated by  via the time-independent Schrödinger equation, which is the following eigenvalue problem for

via the time-independent Schrödinger equation, which is the following eigenvalue problem for  :

:

In Dirac notation, this general eigenvalue problem statement does not yet specify a `language’ in which to express the solutions. We can cast the eigenvalue problem into  -space by introducing the bra

-space by introducing the bra  and expressing the operator

and expressing the operator  in

in  -language. We get the time-independent Schrödinger equation as the second-order differential equation

-language. We get the time-independent Schrödinger equation as the second-order differential equation

This is a well-known differential equation in disguise. The general form is

It is easily seen that (53) becomes (54) if we take

and

The solutions of (54) are stated in terms of the Hermite polynomials,  ,

,  ,

,  ,

,  . The solutions in terms of

. The solutions in terms of  are

are

where only solutions with nonnegative integer values of  make

make  square-integrable, so only these solutions are allowable. We see that

square-integrable, so only these solutions are allowable. We see that  is indeed quantized, i.e., indexed by nonnegative integers

is indeed quantized, i.e., indexed by nonnegative integers  , so if we wanted to we could write

, so if we wanted to we could write  as

as  to emphasise the relevant energy index. The

to emphasise the relevant energy index. The  sequence of energies means that

sequence of energies means that  can never be zero for the quantum harmonic oscillator, and it can only go up in discrete steps of

can never be zero for the quantum harmonic oscillator, and it can only go up in discrete steps of  from its minimum value of

from its minimum value of  . Also note that, as stated earlier, the ladder of

. Also note that, as stated earlier, the ladder of  values is not degenerate for the quantum harmonic oscillator (unlike the particle in a ring model) because only nonnegative integers

values is not degenerate for the quantum harmonic oscillator (unlike the particle in a ring model) because only nonnegative integers  yield valid solutions for this particular eigenvalue problem.

yield valid solutions for this particular eigenvalue problem.

The quantum harmonic oscillator is also used to introduce additional quantum concepts such as quantum tunnelling (the probability amplitudes  are nonzero outside the quadratic potential well for this model, so there is a nonzero probability that the quantum particle can be found outside the potential well. This would be impossible for the classical harmonic oscillator). Another thing to observe here is that it is also possible to cast the eigenvalue problem in

are nonzero outside the quadratic potential well for this model, so there is a nonzero probability that the quantum particle can be found outside the potential well. This would be impossible for the classical harmonic oscillator). Another thing to observe here is that it is also possible to cast the eigenvalue problem in  -language instead of

-language instead of  -language (resulting in expressions for the probability amplitudes

-language (resulting in expressions for the probability amplitudes  which are isomorphic to those for

which are isomorphic to those for  ), and in energy-level language, which introduces the ideas of creation and annihilation operators (also known as raising and lowering operators, respectively, or as ladder operators), as well as commutators. These are nonphysical operators, i.e., they do not correspond to observables, but rather are regarded as useful computational aids.

), and in energy-level language, which introduces the ideas of creation and annihilation operators (also known as raising and lowering operators, respectively, or as ladder operators), as well as commutators. These are nonphysical operators, i.e., they do not correspond to observables, but rather are regarded as useful computational aids.

The annihilation operator  for the quantum harmonic oscillator can be defined in terms of

for the quantum harmonic oscillator can be defined in terms of  and

and  as

as

and the creation operator is its hermitian conjugate

These can be derived from the Hamiltonian operator by pseudo-factorising it. See my previous note about this. From these two equations, we can show that their commutator is unity, i.e.,

![[\hat{a}, \hat{a}^{\dag}] = \hat{a} \hat{a}^\dag - \hat{a}^{\dag} \hat{a} = 1 \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (60)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7Ba%7D%2C+%5Chat%7Ba%7D%5E%7B%5Cdag%7D%5D+%3D+%5Chat%7Ba%7D+%5Chat%7Ba%7D%5E%5Cdag+-+%5Chat%7Ba%7D%5E%7B%5Cdag%7D+%5Chat%7Ba%7D+%3D+1+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2860%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

and the Hamiltonian operator itself can now be re-expressed in terms of these ladder operators as

We also find

![[\hat{a}, \hat{H}] = \hbar \omega \hat{a} \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (62)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7Ba%7D%2C+%5Chat%7BH%7D%5D+%3D+%5Chbar+%5Comega+%5Chat%7Ba%7D+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2862%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

![[\hat{a}^{\dag}, \hat{H}] = -\hbar \omega \hat{a}^{\dag} \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (63)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7Ba%7D%5E%7B%5Cdag%7D%2C+%5Chat%7BH%7D%5D+%3D+-%5Chbar+%5Comega+%5Chat%7Ba%7D%5E%7B%5Cdag%7D+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2863%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

These results allow us to avoid all mention of  and

and  when investigating the energy measurement space generated by the operator

when investigating the energy measurement space generated by the operator  in the eigenvalue problem given as equation (52) above. We have

in the eigenvalue problem given as equation (52) above. We have

![[\hat{a}, \hat{H}] | E \rangle = \hbar \omega \hat{a} | E \rangle](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7Ba%7D%2C+%5Chat%7BH%7D%5D+%7C+E+%5Crangle+%3D+%5Chbar+%5Comega+%5Chat%7Ba%7D+%7C+E+%5Crangle&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

and thus

so

Similarly, from

![[\hat{a}^{\dag}, \hat{H}] | E \rangle = -\hbar \omega \hat{a}^{\dag} | E \rangle](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7Ba%7D%5E%7B%5Cdag%7D%2C+%5Chat%7BH%7D%5D+%7C+E+%5Crangle+%3D+-%5Chbar+%5Comega+%5Chat%7Ba%7D%5E%7B%5Cdag%7D+%7C+E+%5Crangle&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

we have

and so

Therefore,  applied to

applied to  produces a new eigenket

produces a new eigenket  which is lowered in energy by

which is lowered in energy by  . Similarly,

. Similarly,  produces an eigenket raised in energy by

produces an eigenket raised in energy by  . As mentioned earlier, we can use the integer index

. As mentioned earlier, we can use the integer index  to label the energy states instead of

to label the energy states instead of  , i.e., we can write

, i.e., we can write  instead of

instead of  . To make the ladder effect of the creation and annihilation operators even more obvious, we can then write

. To make the ladder effect of the creation and annihilation operators even more obvious, we can then write

and try to work out the eigenvalues  and

and  . The value of

. The value of  can be deduced by noting that applying

can be deduced by noting that applying  in the form of (61) above to

in the form of (61) above to  and using (55) we get

and using (55) we get

which reduces to

But  , so we must have

, so we must have  . Therefore (66) can be written explicitly as

. Therefore (66) can be written explicitly as

We now use this result to deduce the value of  by writing it as

by writing it as

Adding a bra  gives us a self-space bracket on the right-hand side:

gives us a self-space bracket on the right-hand side:

But  , so for (68) to be nonzero we must have

, so for (68) to be nonzero we must have  , so

, so  , and notice that this must also be true for

, and notice that this must also be true for  to be nonzero, so

to be nonzero, so  and

and  must both represent the same function. With these insights, we can re-express (68) as

must both represent the same function. With these insights, we can re-express (68) as

Taking the hermitian conjugate of both sides of (69) gives

from which we deduce that the explicit form of (67) must be

i.e.,  . Thus, we have

. Thus, we have

Quantum particle on a spherical shell

We now extend the model further by introducing two-dimensional quantum states for a quantum particle on a spherical shell. The general approach to modelling is similar to the approach for the harmonic oscillator in a number of ways. In particular, we begin by setting up a classical model of a particle on a sphere, and then quantize it by considering the relevant quantum mechanical operators in a quantum version of the model.

In a classical model of a particle on a spherical shell, the particle is constrained to positions at a fixed distance  from the origin, but can otherwise move anywhere on a spherical surface. In the previous quantum particle in a ring model,

from the origin, but can otherwise move anywhere on a spherical surface. In the previous quantum particle in a ring model,  was assumed to be sufficiently large to enable angular momentum considerations to be ignored, and the focus was then on linear momentum

was assumed to be sufficiently large to enable angular momentum considerations to be ignored, and the focus was then on linear momentum  . In the present particle on a spherical shell model, we no longer assume

. In the present particle on a spherical shell model, we no longer assume  is large and in fact the particle now only has angular momentum. As discussed in a previous post involving angular momentum calculations, the classical particle has a vector angular momentum about the origin given by

is large and in fact the particle now only has angular momentum. As discussed in a previous post involving angular momentum calculations, the classical particle has a vector angular momentum about the origin given by

which has components

There is no potential energy in this model, only kinetic energy, but the constraint that the particle must remain on the spherical shell means that  and

and  are always orthogonal, so

are always orthogonal, so

This linear constraint means that only two of the three linear momentum components are linearly independent, so the linear momentum space for this model is two-dimensional. In view of (71) and (75), the magnitudes of the linear and angular momentum are related by

so

Therefore, the Hamiltonian for the classical particle in a shell model is

Using spherical coordinates, the classical particle can wander anywhere on the sphere, with any angular momentum in any direction, its position characterised by the polar angle  and the azimuthal angle

and the azimuthal angle  . In the case of a quantum particle on a spherical shell, a position measurement defines a two-dimensional basis space and a position state would be denoted by the ket

. In the case of a quantum particle on a spherical shell, a position measurement defines a two-dimensional basis space and a position state would be denoted by the ket  . There would be two quantum operators

. There would be two quantum operators  and

and  whose eigenvalues are the spectra of possible

whose eigenvalues are the spectra of possible  and

and  values respectively, and a single eigenstate

values respectively, and a single eigenstate  is now regarded as a simultaneous solution of the two eigenvalue problems for these operators:

is now regarded as a simultaneous solution of the two eigenvalue problems for these operators:

This is possible if and only if  and

and  commute, i.e.,

commute, i.e., ![[\hat{\theta}, \hat{\varphi}] = 0](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7B%5Ctheta%7D%2C+%5Chat%7B%5Cvarphi%7D%5D+%3D+0&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002) . Operators which commute are called compatible operators and they must have simultaneous eigenstates. Conversely, two operators which have simultaneous eigenstates must commute. (An indication of why this is true is as follows. Suppose we are given the eigenvalue equation (78), so that

. Operators which commute are called compatible operators and they must have simultaneous eigenstates. Conversely, two operators which have simultaneous eigenstates must commute. (An indication of why this is true is as follows. Suppose we are given the eigenvalue equation (78), so that  is an eigenstate of

is an eigenstate of  with eigenvalue

with eigenvalue  . Then, given

. Then, given ![[\hat{\theta}, \hat{\varphi}] = 0](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7B%5Ctheta%7D%2C+%5Chat%7B%5Cvarphi%7D%5D+%3D+0&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002) , we must have

, we must have

Therefore, both  and

and  are eigenstates of

are eigenstates of  with the same eigenvalue

with the same eigenvalue  , so they must represent the same eigenstate up to some proportionality constant. The fact that

, so they must represent the same eigenstate up to some proportionality constant. The fact that  and

and  represent the same eigenstate up to a proportionality constant is exactly what (79) says). The fact that this condition holds means that the measurement of an eigenvalue of

represent the same eigenstate up to a proportionality constant is exactly what (79) says). The fact that this condition holds means that the measurement of an eigenvalue of  does not destroy knowledge of an eigenvalue of

does not destroy knowledge of an eigenvalue of  , and vice versa. This is not possible with all pairs of measurements. For example, the operators

, and vice versa. This is not possible with all pairs of measurements. For example, the operators  and

and  are incompatible and thus do not have simultaneous eigenstates, so no two-dimensional state such as

are incompatible and thus do not have simultaneous eigenstates, so no two-dimensional state such as  exists. Knowledge of

exists. Knowledge of  would be destroyed by a measurement of

would be destroyed by a measurement of  , and vice versa. This is indicated by the fact that

, and vice versa. This is indicated by the fact that  and

and  do not commute, since

do not commute, since ![[\hat{x}, \hat{p}] = i \hbar \neq 0](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7Bx%7D%2C+%5Chat%7Bp%7D%5D+%3D+i+%5Chbar+%5Cneq+0&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002) . Simultaneous eigenstates can only exist for operators which commute.

. Simultaneous eigenstates can only exist for operators which commute.

Note that this idea of compatible vs incompatible operators is intimately related to Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle. Given two operators  and

and  , with standard deviations

, with standard deviations  and

and  respectively, the generalised form of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle says

respectively, the generalised form of Heisenberg’s uncertainty principle says

![\Delta a \Delta b \ge \frac{1}{2} |\langle [\hat{A}, \hat{B}] \rangle|](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5CDelta+a+%5CDelta+b+%5Cge+%5Cfrac%7B1%7D%7B2%7D+%7C%5Clangle+%5B%5Chat%7BA%7D%2C+%5Chat%7BB%7D%5D+%5Crangle%7C&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

where ![|\langle [\hat{A}, \hat{B}] \rangle|](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%7C%5Clangle+%5B%5Chat%7BA%7D%2C+%5Chat%7BB%7D%5D+%5Crangle%7C&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002) denotes the absolute value of the expectation of the commutator of

denotes the absolute value of the expectation of the commutator of  and

and  . (The concept of the expectation of an operator is discussed in a later section below). Thus, there is no uncertainty principle for compatible operators, and measurement of one will not affect measurement of the other. However, there is always an uncertainty principle for incompatible operators, i.e., those with non-zero commutators, and it is impossible to measure one without destroying a previous measurement of the other.

. (The concept of the expectation of an operator is discussed in a later section below). Thus, there is no uncertainty principle for compatible operators, and measurement of one will not affect measurement of the other. However, there is always an uncertainty principle for incompatible operators, i.e., those with non-zero commutators, and it is impossible to measure one without destroying a previous measurement of the other.

Recall that in the case of the harmonic oscillator we could solve the eigenvalue problem in  -language,

-language,  -language, or energy-level-language, and the energy-level-language approach gave rise to creation and annihilation operator approaches. Similar considerations apply to the quantum particle on a spherical shell model. We can solve the eigenvalue problem in the language of angular momentum components rather than in the language of spatial or linear momentum states, and this gives rise to ladder operators analogous to the creation and annihilation operators for the quantum harmonic oscillator. Since angular momentum components can be measured, there must be angular momentum state labels and angular momentum operators. The angular momentum operators are simply the classical angular momenta turned into operators by `putting hats on them’. Thus, we get the operators

-language, or energy-level-language, and the energy-level-language approach gave rise to creation and annihilation operator approaches. Similar considerations apply to the quantum particle on a spherical shell model. We can solve the eigenvalue problem in the language of angular momentum components rather than in the language of spatial or linear momentum states, and this gives rise to ladder operators analogous to the creation and annihilation operators for the quantum harmonic oscillator. Since angular momentum components can be measured, there must be angular momentum state labels and angular momentum operators. The angular momentum operators are simply the classical angular momenta turned into operators by `putting hats on them’. Thus, we get the operators

The eigenvalues of  make up the measurement spectrum of the square of the total angular momentum.

make up the measurement spectrum of the square of the total angular momentum.

We know that spatial states  and linear momentum states are two-dimensional, so we must also find that the measurement space created by the angular momentum operators is two-dimensional since dimensionality is conserved, no matter what language is used to describe the system. Indeed, we find that no two of the three angular momentum operators commute with each other:

and linear momentum states are two-dimensional, so we must also find that the measurement space created by the angular momentum operators is two-dimensional since dimensionality is conserved, no matter what language is used to describe the system. Indeed, we find that no two of the three angular momentum operators commute with each other:

![[\hat{L}_x, \hat{L}_y] = i\hbar \hat{L}_z \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (84)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_x%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D_y%5D+%3D+i%5Chbar+%5Chat%7BL%7D_z+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2884%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

![[\hat{L}_y, \hat{L}_z] = i\hbar \hat{L}_x \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (85)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_y%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D_z%5D+%3D+i%5Chbar+%5Chat%7BL%7D_x+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2885%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

![[\hat{L}_z, \hat{L}_x] = i\hbar \hat{L}_y \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (86)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_z%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D_x%5D+%3D+i%5Chbar+%5Chat%7BL%7D_y+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2886%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

Therefore, it is impossible to define eigenstates based on these components. However, all three components do commute with  :

:

![[\hat{L}_x, \hat{L}^2] = [\hat{L}_y, \hat{L}^2] = [\hat{L}_z, \hat{L}^2] = 0 \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (87)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_x%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D%5E2%5D+%3D+%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_y%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D%5E2%5D+%3D+%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_z%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D%5E2%5D+%3D+0+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2887%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

Therefore, it is possible to characterise an eigenstate using  and any one of the components. In what follows, we will use a basis corresponding to the simultaneous eigenstates of

and any one of the components. In what follows, we will use a basis corresponding to the simultaneous eigenstates of  and

and  . Suppose the eigenvalues of

. Suppose the eigenvalues of  are

are  and the eigenvalues of

and the eigenvalues of  are

are  (

( has dimensions of angular momentum, so its presence here enables

has dimensions of angular momentum, so its presence here enables  and

and  to be treated as dimensionless). We now seek to find

to be treated as dimensionless). We now seek to find  and

and  as simultaneous solutions of the two eigenvalue problems

as simultaneous solutions of the two eigenvalue problems

To do this, we define two new operators, the lowering and raising operators  and

and  , which are the analogues of the annihilation and creation operators for the harmonic oscillator:

, which are the analogues of the annihilation and creation operators for the harmonic oscillator:

Note that since  commutes with

commutes with  and

and  , it must also commute with

, it must also commute with  and

and  . We find that

. We find that

![[\hat{L}_{-}, \hat{L}_z] = \hbar \hat{L}_{-} \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (92)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_%7B-%7D%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D_z%5D+%3D+%5Chbar+%5Chat%7BL%7D_%7B-%7D+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2892%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

![[\hat{L}_z, \hat{L}_{+}] = \hbar \hat{L}_{+} \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (93)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D_z%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D_%7B%2B%7D%5D+%3D+%5Chbar+%5Chat%7BL%7D_%7B%2B%7D+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2893%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

and also

![[\hat{L}^2, \hat{L}_{-}] = [\hat{L}^2, \hat{L}_{+}] = 0 \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (94)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D%5E2%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D_%7B-%7D%5D+%3D+%5B%5Chat%7BL%7D%5E2%2C+%5Chat%7BL%7D_%7B%2B%7D%5D+%3D+0+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%2894%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)

Following a similar line of reasoning as with the annihilation and creation operators of the quantum harmonic oscillator, we find that

To find  and

and  , we begin by noting that

, we begin by noting that  since

since  is just one component of

is just one component of  . Therefore,

. Therefore,  is bounded, so there must be a

is bounded, so there must be a  and a

and a  . Let

. Let  . Next, we observe that the existence of the ladder operators in (95) and (96) implies that the eigenvalues

. Next, we observe that the existence of the ladder operators in (95) and (96) implies that the eigenvalues  are discrete, consisting of a ladder of unit steps. Thus, we have

are discrete, consisting of a ladder of unit steps. Thus, we have

for some  , and therefore

, and therefore

We next observe that

because the minimum state cannot be lowered further and the maximum state cannot be raised further. We also observe that  can be expressed in terms of

can be expressed in terms of  and

and  in two different ways:

in two different ways:

We now apply (100) to the state  , using (98), (88) and (89), and we get

, using (98), (88) and (89), and we get

Similarly, applying (101) to the state  using (99) we get

using (99) we get

From (102) and (103) we get

which implies

We conclude from (103) and (104) that  in (88), where the allowed spectrum of

in (88), where the allowed spectrum of  values are the nonnegative half-integers:

values are the nonnegative half-integers:

And  runs from

runs from  to

to  in integer steps. Using these results in (88) and (89), and using

in integer steps. Using these results in (88) and (89), and using  to label an eigenstate of

to label an eigenstate of  instead of

instead of  , we conclude

, we conclude

where  is an integer and

is an integer and  runs from

runs from  to

to  in integer steps:

in integer steps:

Finally, to find  in (95), we apply (100) to the state

in (95), we apply (100) to the state  to get

to get

which implies

Taking  to be real, we get

to be real, we get

and

Therefore, the effects of the lowering and raising operators are

So far, we have worked out the quantum particle in a spherical shell model using the language of angular momentum,  . We can also use the language of position,

. We can also use the language of position,  , and in fact we can work out the transformation matrix elements

, and in fact we can work out the transformation matrix elements  which also have the physical interpretation of being probability amplitudes for finding the quantum particle at position

which also have the physical interpretation of being probability amplitudes for finding the quantum particle at position  when it is known to be in angular momentum state

when it is known to be in angular momentum state  . This exercise will reveal the crucial fact that

. This exercise will reveal the crucial fact that  in (105) can only take integer values in the case of orbital angular momentum.

in (105) can only take integer values in the case of orbital angular momentum.

We first of all cast (106) and (107) in the language of  by introducing a bra

by introducing a bra  :

:

To implement these equations, we need  and

and  , i.e., we need the operators

, i.e., we need the operators  and

and  expressed in the language of

expressed in the language of  . I obtained these expressions as well as expressions for

. I obtained these expressions as well as expressions for  and

and  in a previous post. We can also use these to get expressions for

in a previous post. We can also use these to get expressions for  and

and  . Using

. Using

in (112) we get a differential equation

And using

in (111) we get a second differential equation

The transformation matrix elements  are the simultaneous solutions of these two differential equations. From (113) we deduce that

are the simultaneous solutions of these two differential equations. From (113) we deduce that

where  is some function of

is some function of  . This equation is crucial because it reveals that

. This equation is crucial because it reveals that  can only take integer values. This is a necessary condition for

can only take integer values. This is a necessary condition for  to be periodic with respect to

to be periodic with respect to  , which it must be. But by (108) this in turn implies that

, which it must be. But by (108) this in turn implies that  can only take integer values in the case of orbital angular momentum. The half-integer values in (105) must relate to something other than orbital angular momentum and will be found below to correspond to quantum mechanical spin angular momentum.

can only take integer values in the case of orbital angular momentum. The half-integer values in (105) must relate to something other than orbital angular momentum and will be found below to correspond to quantum mechanical spin angular momentum.

Using (115) in (114) we get a well-known differential equation:

This is satisfied by the associated Legendre polynomials,  . These are the functions

. These are the functions  in (115). Using

in (115). Using  to construct properly normalized simultaneous solutions to (113) and (114) we obtain finally

to construct properly normalized simultaneous solutions to (113) and (114) we obtain finally

where the functions  are well-known tabulated functions called the spherical harmonic functions. Interestingly, these functions characterise the normal mode standing waves of the vibrations of a spherical shell, i.e., the fundamental and all the harmonics of a spherical drumhead. They are the two-dimensional analogues on a sphere of one-dimensional sines and cosines (the harmonic functions for a line). The correct normalization constants for the probability amplitudes in (117) would be found using the certainty condition, which in spherical coordinates is

are well-known tabulated functions called the spherical harmonic functions. Interestingly, these functions characterise the normal mode standing waves of the vibrations of a spherical shell, i.e., the fundamental and all the harmonics of a spherical drumhead. They are the two-dimensional analogues on a sphere of one-dimensional sines and cosines (the harmonic functions for a line). The correct normalization constants for the probability amplitudes in (117) would be found using the certainty condition, which in spherical coordinates is

Spin, Pauli spin matrices and matrix mechanics

The angular momentum of a circulating charged particle gives rise to a magnetic dipole moment. This concept is usually first encountered in elementary electromagnetism when considering the torque on a current loop immersed a magnetic field  , which is given by

, which is given by

where

is the magnetic dipole moment. Here,  is the number of turns in the current loop,

is the number of turns in the current loop,  is the conventional current flowing through the loop (i.e., the rate at which positive charge is flowing through a cross-section of the conducting loop),

is the conventional current flowing through the loop (i.e., the rate at which positive charge is flowing through a cross-section of the conducting loop),  is the area enclosed by the current loop and

is the area enclosed by the current loop and  is a unit vector which is normal to the plane of the area

is a unit vector which is normal to the plane of the area  in the sense given by the right-hand rule. (The direction of the normal unit vector would be the reverse of that indicated by the right-hand rule if a negative charge flow was being considered).

in the sense given by the right-hand rule. (The direction of the normal unit vector would be the reverse of that indicated by the right-hand rule if a negative charge flow was being considered).

In the case of a classical charged particle of mass  and positive charge

and positive charge  circulating around a spherical shell of radius

circulating around a spherical shell of radius  with speed

with speed  , we have

, we have  ,

,  ,

,  , and

, and  , so the magnitude of the magnetic dipole moment is obtained as

, so the magnitude of the magnetic dipole moment is obtained as

where  and

and  are the magnitudes of the linear and angular momenta of the orbiting charged particle respectively. In vector form, we have

are the magnitudes of the linear and angular momenta of the orbiting charged particle respectively. In vector form, we have

where the vectors point in a direction given by the right-hand rule. Thus, we see that the magnetic dipole moment is directly proportional to the angular momentum of the orbiting charged particle, with the constant of proportionality involving the charge-to-mass ratio of the particle.

Based on the link between magnetic dipole moment and angular momentum exhibited in (121), we would expect that the magnetic dipole moment of a quantum charged particle, e.g., an electron, say in the  -direction of a coordinate system, would be related to the operators

-direction of a coordinate system, would be related to the operators  and

and  in (106) and (107) above with their discrete spectra of eigenvalues. This is indeed the case. The iconic Stern-Gerlach experiment of 1922 was designed to measure the magnetic dipole moments of quantum particles and indeed found that these were quantized in accordance with the relationship suggested by (121) and the operators

in (106) and (107) above with their discrete spectra of eigenvalues. This is indeed the case. The iconic Stern-Gerlach experiment of 1922 was designed to measure the magnetic dipole moments of quantum particles and indeed found that these were quantized in accordance with the relationship suggested by (121) and the operators  and

and  discussed in the previous section. For example, the Stern-Gerlach apparatus produced discrete line spectra when measuring the

discussed in the previous section. For example, the Stern-Gerlach apparatus produced discrete line spectra when measuring the  component of magnetic dipole moment, rather than continuous spectra which would have been expected classically, with the multiplicities of the discrete line spectra corresponding exactly to the multiplicities of the eigenvalues

component of magnetic dipole moment, rather than continuous spectra which would have been expected classically, with the multiplicities of the discrete line spectra corresponding exactly to the multiplicities of the eigenvalues  in (108) for given values of

in (108) for given values of  . In other words, for any given value of

. In other words, for any given value of  , the multiplicity of the discrete line spectra produced by the Stern-Gerlach apparatus was

, the multiplicity of the discrete line spectra produced by the Stern-Gerlach apparatus was  in accordance with (108).

in accordance with (108).

It was noted in the previous section that  can only take integer values in the case of orbital angular momentum, so if magnetic dipole moments were due only to orbital angular momentum the multiplicities

can only take integer values in the case of orbital angular momentum, so if magnetic dipole moments were due only to orbital angular momentum the multiplicities  of the discrete line spectra produced by the Stern-Gerlach apparatus would always be odd numbers. However, this is not what was observed. Famously, a two-line spectrum was produced for the magnetic dipole moment of a beam of free electrons which had no orbital angular momentum at all. The two-line spectrum corresponded to eigenvalues

of the discrete line spectra produced by the Stern-Gerlach apparatus would always be odd numbers. However, this is not what was observed. Famously, a two-line spectrum was produced for the magnetic dipole moment of a beam of free electrons which had no orbital angular momentum at all. The two-line spectrum corresponded to eigenvalues  in (108) of

in (108) of  and

and  , and this is only possible if

, and this is only possible if  . Eventually, this result came to be understood as signifying that electrons have an intrinsic spin angular momentum which also produces its own magnetic dipole moment quite distinct from any magnetic moment due to orbital angular momentum. The difference between them is that while it is possible to have nonzero probability amplitudes

. Eventually, this result came to be understood as signifying that electrons have an intrinsic spin angular momentum which also produces its own magnetic dipole moment quite distinct from any magnetic moment due to orbital angular momentum. The difference between them is that while it is possible to have nonzero probability amplitudes  for orbital angular momentum with integer values of

for orbital angular momentum with integer values of  , such probability amplitudes must always be zero for spin angular momentum with

, such probability amplitudes must always be zero for spin angular momentum with  equal to a half-integer. Spin angular momentum simply has no representation in real physical space, so spin states cannot be cast into

equal to a half-integer. Spin angular momentum simply has no representation in real physical space, so spin states cannot be cast into  language.

language.

The convention is to use the letter  rather than

rather than  to denote spin parameter values, and we always have

to denote spin parameter values, and we always have  in the case of the electron (we say the electron spin quantum number is

in the case of the electron (we say the electron spin quantum number is  ). Apart from this, however, spin angular momentum operators obey exactly the same rules that were outlined for angular momentum in the previous section. We have a spin vector

). Apart from this, however, spin angular momentum operators obey exactly the same rules that were outlined for angular momentum in the previous section. We have a spin vector  from whose components the operators

from whose components the operators  ,

,  and

and  are built, exactly like

are built, exactly like  and the operators

and the operators  ,

,  and

and  . Also, by (84)-(87) above we have

. Also, by (84)-(87) above we have

![[\hat{S}_x, \hat{S}_y] = i\hbar \hat{S}_z \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad \qquad (122)](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=%5B%5Chat%7BS%7D_x%2C+%5Chat%7BS%7D_y%5D+%3D+i%5Chbar+%5Chat%7BS%7D_z+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%5Cqquad+%28122%29&bg=ffffff&fg=111111&s=0&c=20201002)